Light Vessel Automatic

Tate Britain, London UK - February 2013

Tate Britain is a richly adorned vessel of knowledge, literally scarred and marked by its own history. From its geological birth as an Eyot at the fork of the river Tyburn, to locus of panoptic surveillance systems of the Millbank Penitentiary, to National Gallery of Art, it continues to undergo further phases of transformation.

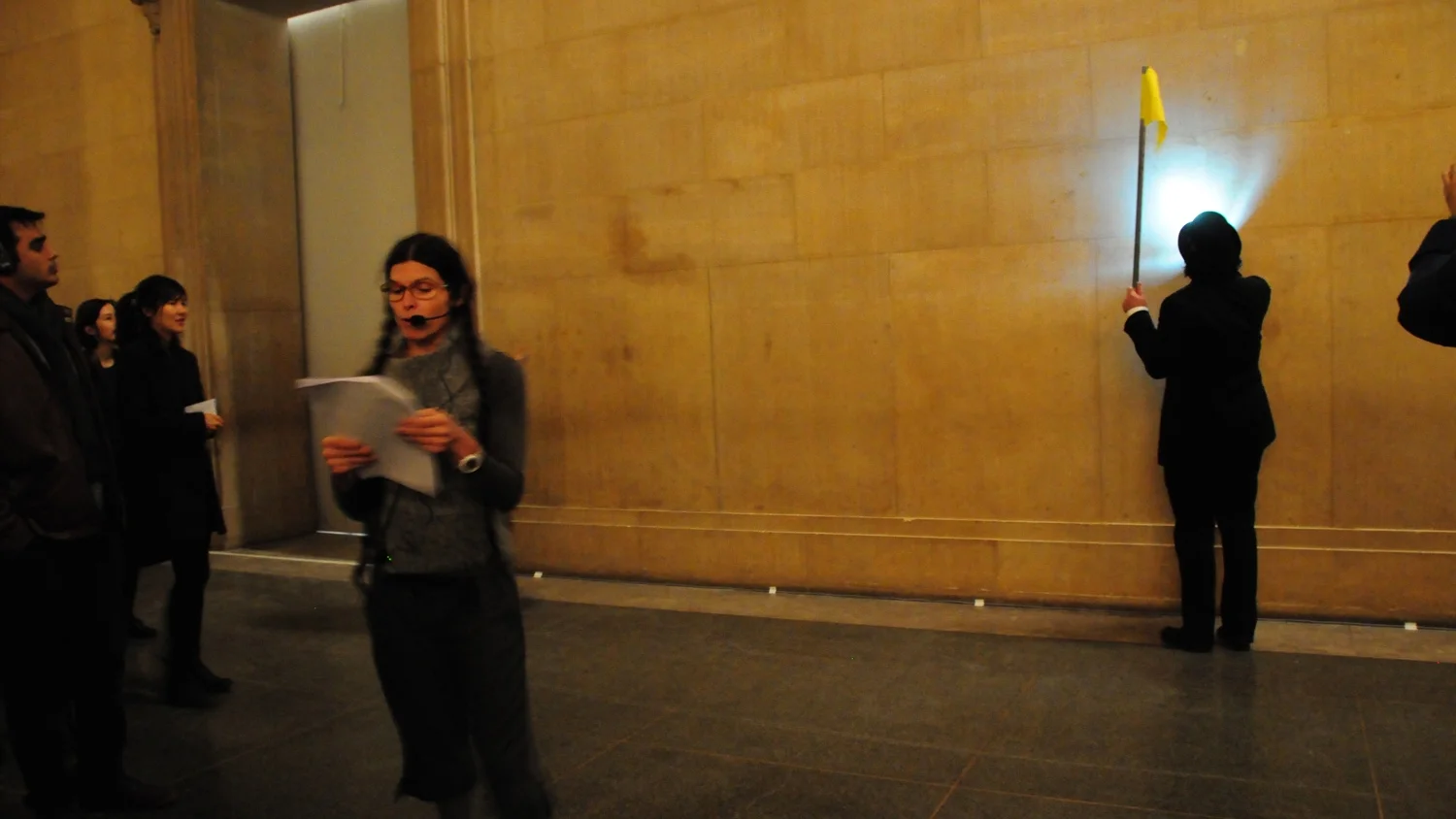

In Light Vessel Automatic, we conduct a guided tour en-promenade through the Tate, moving between specific details of the building’s fabric to wider historical, political, philosophical and aesthetic concerns. Through spoken word, moving image, word & image, and architectural elements we explore the site as a fulcrum for a number of inter-related systems. These systems reveal a series of interlocking narrative threads that coalesce around the site, entangling its history and forming a foundational mesh for its future potential.

This project was curated by Marianne Mulvey as part of the 'Performing Architecture' event at Tate Britain. Artists involved include Kreider + O'Leary - Alex Sweder - Lamis Bayer - Emptyset - Film Programme by the Architecture Foundation. Marianne's blog on the curation of the event is here. Thanks to Caruso St John Architects for guiding us around the Tate under construction. An on-line version of the guided tour is documented below.

PROLOGUE

Somewhere. Outside. It was and it was not. From ether, air was born. From the air, fire was born. From the fire, water was born. (Pooling. Circulating. Dividing.) From the water, earth was born.

So now here, where we are standing, layers of:

mudstone –

sandstone –

impermeable Gault clay –

a non-contiguous layer of Upper Greensand –

a rolling bed of white chalk –

fossilized shell fragments –

flints –

stiff, grey-blue London Clay –

sand & gravel terraces made up of flint, quartz and quartzite –

deposits of brickearth –

deposits of hundreds of years of human occupation –

concrete foundation –

brick basement walls –

stone floor.

Geology determined why this, rather than anywhere else along the Thames, became the chosen spot.

I. EYOT

During the First Century AD, the largest river in Britain was fed by streams from thickly wooded hills that, now, we call Highgate and Hampstead. One such stream, the Tyburn, arose from a confluence of two tributaries; the Tyburn, itself, branched into two distributaries somewhere between St. James Park and Buckingham Palace. So arose this place of division: the ‘y’ between the letters ‘e’ and ‘o’ in the word /eyot/.

eyot, n. : British dialect an islet, esp. in a river

[Origin: before 900 and ‘the great vowel shift’; Middle English eyt, Old English ӯgett, diminutive of ieg, īg island.]

An island (of sorts) covered in thorns. Eyot of Thorns or Thorn-ey Island. Here, where we are standing. This ‘terrible place’.

Here has a poetics: its metonym a tree rooted upstream and in history. There, in 1196, a body swung, pendularly shifting from ‘I’ to ‘Not-I’; a suspense between Spectacle and Law. Then, there, in 1571, the Tyburn Tree was erected: a novel form of gallows that was used for mass executions. Functioning as both apparatus and symbol of the Law, this was called “Triple Tree” or, more simply, "Tree".

II. PANOPTICON

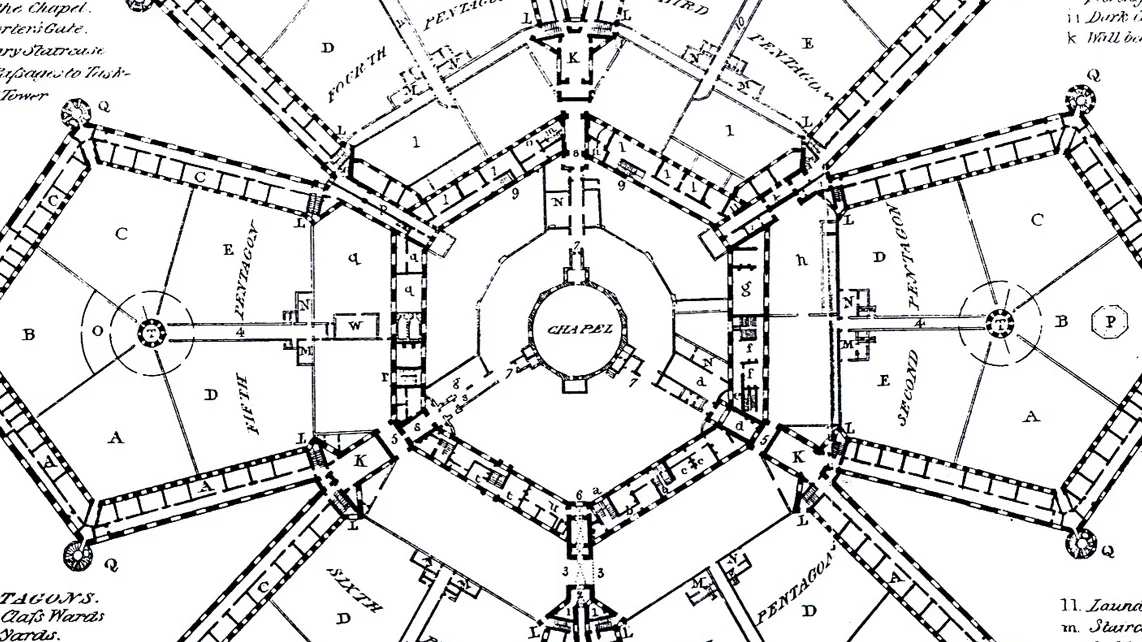

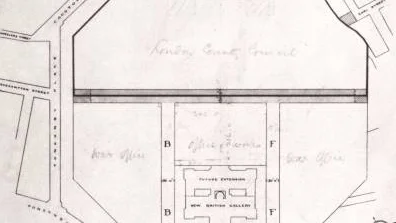

An octagon is a closed geometric figure with eight sides of the same length and internal angles of the same size. The octagon shape characterises umbrellas, Vichy Pastilles, Japanese lottery machines and stop signs in most English speaking countries, and in Europe. This particular octagon – here, where we are standing – is the result of a circular dome being placed on top of the gallery’s central linear axes: a central axis that, itself, maps directly onto that of its architectural precedent.

Now forgets our tree, our mass spectacle, our gruesome death.

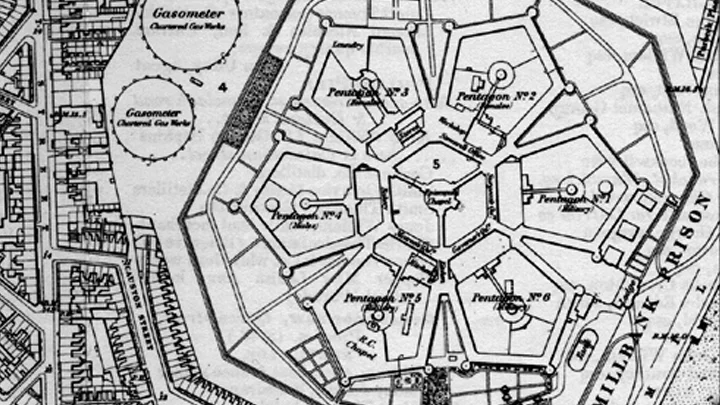

Built on this same ground, Millbank Prison was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. The prison’s architectural plan comprised a central circular chapel surrounded by a three-storey hexagon whose interior and exterior angles, like that of an octagon, are equivalent, and whose geometry characterises, for example, beehive honeycombs, the scutes of a turtle's carapace and a polar cloud on Saturn. (Metropolitan France also has a vaguely hexagonal shape.) Radiating out from Millbank Prison’s central circle and hexagon were six pentagons of cell blocks set around a cluster of courtyards.

From a bird’s eye, it looks like a flower: a flower with six petals and no thorns ...

Millbank Prison was originally intended as a Panopticon: the embodiment of philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s architectural ideal of a new ‘penitentiary’ system, with individual cells made visible at all times. Conceivably, the awareness of being continuously the object of a powerful and disciplinary gaze would encourage law-abiding, good behaviour in prisoners not through fear of repercussion, but through an internalised sense of the mechanics of power; the psychology of surveillance.

Flora of confined sentences uttered voiceless under the auspice of an all-seeing Eye ...

While the Panopticon model was ideal, the Millbank site was not: too marshy, unhealthy and small for Bentham’s project, which was thwarted in 1799. The penitentiary eventually built, designed by William Williams, owed little to Bentham’s original plan for a Panopticon beyond the fact that the governor's quarters, administrative offices, and chapel were all placed at the centre of the complex – here, were we are standing.

III. X

A. WAR

X marks the Axis trace bird’s eye, bomb run, bomb drop trajectory slip straight through strategic sky ceiling arched destruction deep floor — foundation yawning — debris. Rubble everywhere. Including here, where we are standing.

'Early one morning I was awoken by a terrific explosion to feel the massive building violently shaking and to hear an avalanche of masonry and glass... Since the raid was still in progress we could not use our torches, but by the inadequate light of the stars and bursting shells we crept through the wreckage from room to room, cautiously, because the firing of the A.A guns brought down cascades of loosened roof glass. Outside the building on the east side, what half an hour before had been a road, pavement, lawn, and flowerbeds was now merged in one indistinguishable desolation...'

– John Rothenstein, Director of Tate, Museum Journal, December 1940

Unintended military aesthetic; material by-product of psychological warfare. Clear it up. Move the art. Boil the kettles.

B. LOGOS

X marks the name Joseph DUVEEN, 1st Baron DUVEEN of Millbank (1869-1939). LOFTY. STONY. HAUGHTY. DUVEEN SCULPTURE GALLERIES were the first galleries built specifically for sculpture in ENGLAND. POMPOUS. GRAND. DUVEEN also gave money to the BRITISH MUSEUM in order to build there a DUVEEN GALLERY specifically for the marbles of ELGIN. DIRTY. DUVEEN did not think the marbles WHITE enough for exhibition – ‘the sculptures should be made as clean and WHITE as possible’ – so ordered them to be cleaned with carborundum and copper brushes, scraping off the surfaces to get to something WHITE. CRIMINAL.

Meanwhile, now, behind the blind door and wall held in suspense:

LIGHT

VESSEL

AUTOMATIC

IV. REVERBERATION

1967 sees the Summer of Love and also the move to New York, just weeks before graduating high school, of young gospel singer and future pop icon Donna Summer, who auditions for a role in the musical Hair that, with its opening song ‘Aquarious’, brings worldwide attention to the Age of Aquarious, hippie and New Age cultural movements of the 1960’s and 70’s, but when Melba Moore is cast instead, Summer moves to London for Hair’s UK production, during which time she briefly lives on Erasmus street, just around the corner from, here, the Tate Britain, before moving on to Munich as part of Hair’s German production where, recording background vocals for Three Dog Night in Musicland Studios, she meets German-based producers Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte, and later records the final, futuristic section of an album entitled The Four Seasons of Love, for which an accidental overdub using a Moog synthesizer harnessed to a 16-track Studer A80 generates a baseline so pioneering that it prompts Brian Eno to say “[t]his single is going to change the sound of club music for the next 15 years,” which it does, revolutionising disco and altering the course of electronic music since its release in 1977 to now.

V. KALEIDOSCOPE

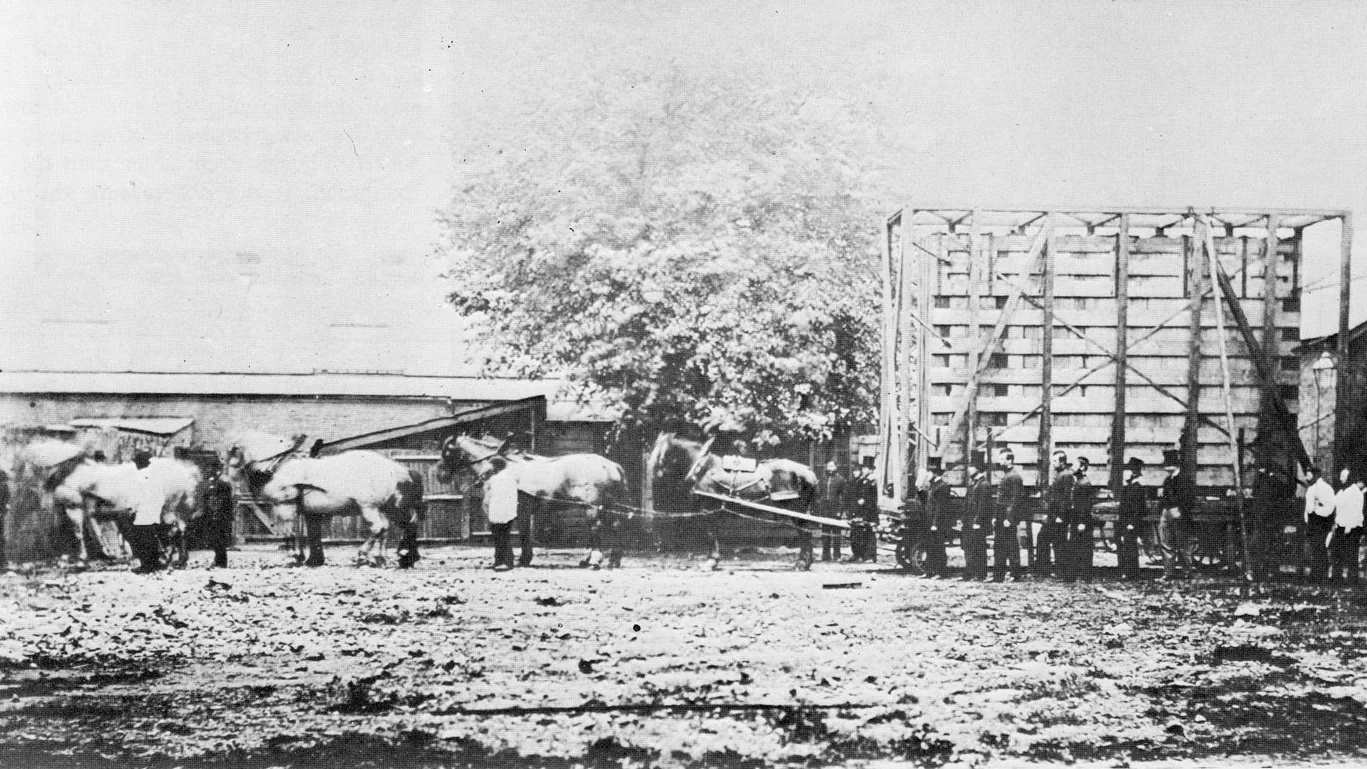

There is the sound of something very heavy being dragged. Can you hear it? All weight and woody fibres as the infinitesimal space between it and the cold stone floor fills with friction. Long, a-rhythmic stretches breached occasionally by the staccato of clodded horse feet. These vibrations strike our tympanum, announcing the arrival of the art.

O! arrival of the art. O! arched gate. O! river run. O! mumbling flotilla. Waterway penal colony. O! hexagon.

Difficult to see on this map, perhaps easier to fabricate. So the thorns become part of an intricate pattern:

axis to circle ;

circle to stem ;

stem to octagon ;

octagon to leaf ;

leaf to hexagon ;

hexagon to stamin ;

stamin to polygon ;

polygon to pistol.

You trace the lines with your fingertips, slowly sounding their vegetal way along which, and barely visible, way farers have passed and, with this, paths have morphed from desire into cartography. (O! trade route.) It thus becomes a matter of perspective:

From one view the sky looks expansive and, from another, Gothically lined. (O! viaduct.)

So, now, with hands clasped together in penitential prayer, line to secreted line on handscape, another life becomes history. (O! Animals and fish.)

VI. ICON

‘There is no money that is completely pure.’

– Nicholas Serota, Director of the Tate

Like the sun.

Like a flower.

Like an asterisk.*

Like an ice crystal melting in the Arctic.

Like that same ice crystal transported from the Arctic by Liberate Tate and melting in Tate Modern to trace a line of connection from BP’s devastating impacts on ecosystems, communities and the global climate to Tate.

This icon is a point on that line of connection.

That line continues through the history of Tate benefaction connecting BP with Charles Clore, Joseph Duveen and Henry Tate.

A picture now emerges.

It looks nothing like a flower or the sun.

A flower looks nothing like commerce or a plantation.

The sun looks nothing like a thick, black ocean.

* Consistent with the principles outlined in Section 2.2 of its Ethics Policy, Tate will not accept funds in circumstances when: ‘b. The donor has acted, or is believed to have acted, illegally in the acquisition of funds, for example when funds are tainted through being the proceeds of criminal conduct.’

VII. CLOUD

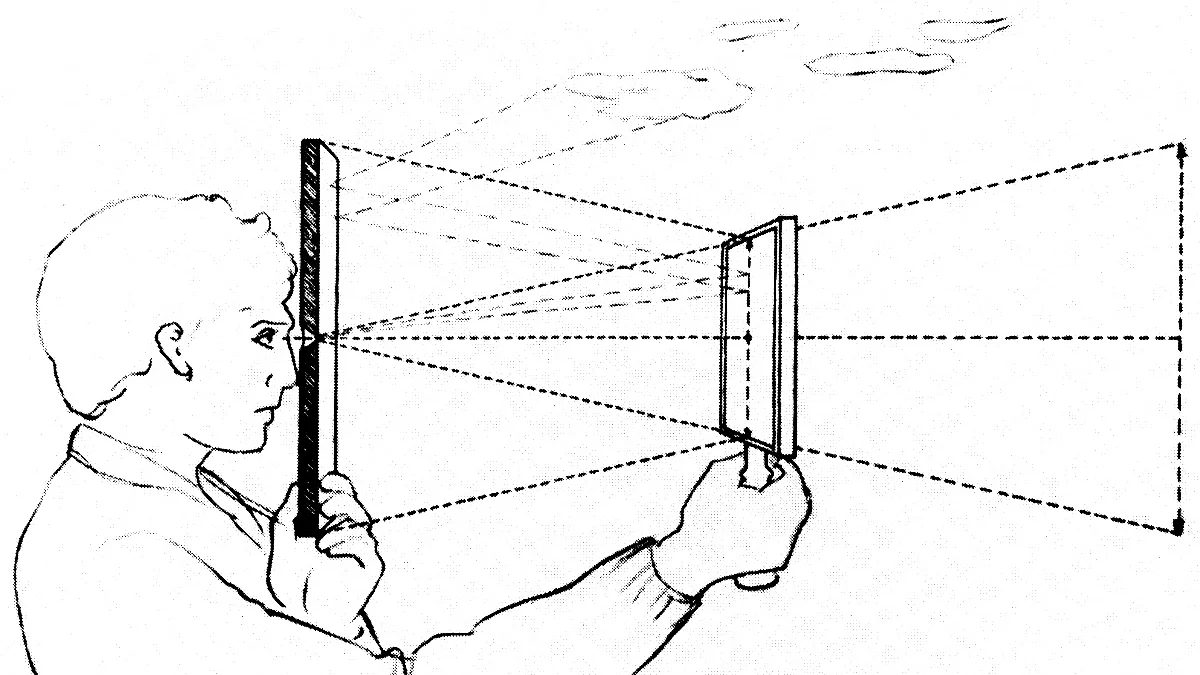

In Theory of /Cloud/: Toward a History of Painting (1972), art historian Hubert Damisch argues that perspectival art in the West is a semiotic system predicated on an act of exclusion. To make his point, Damisch refers to one of Fillippo Brunelleschi’s early experiments with perspective. In generating this experiment, Brunelleschi first depicted the baptistery of San Giovanni on the surface of a panel using single point perspective. He then cut a peephole into this panel at the vanishing point of the perspectival composition. As a result, a viewer standing behind the panel, and holding up a mirror to its front, could view the depicted architectural scene – through the mirror – where it appeared in perfect perspective. In this early experiment, Brunelleschi represented all of the buildings as painted images in single point perspective; however, as Damisch notes:

Brunelleschi made no attempt to depict [the] sky; he merely showed it (dimostrare). And, in order to do so, he resorted to a subterfuge that introduces into the representational circuit a direct reference to external reality, and at the same time a supplementary reduplication of the specular structure upon which the experiment was founded. (Damisch 123)

What, exactly, was Brunelleschi’s act of representational ‘subterfuge’ that, for Damisch, carries such ramifications for the perspectival system? To explicate this, Damisch refers to Antonio Manetti’s biography Vita di Filippo Brunelleschi (c. 1480) where Manetti describes Brunelleschi’s act in detail: “As he [Brunelleschi] had to show the sky on which the walls shown in perspective were stamped, he put darkened silver so that the natural air and sky would be mirrored there, and also the clouds to be seen in the air, pushed along by wind when it blew” (Damisch, footnote 114, 280). In other words, rather than pictorially depict the sky, Brunelleschi added a reflective material to the surface of the panel that would, in fact, mirror the ‘real’ sky.

According to Damisch, this mirrored sky in Brunelleschi’s experiment testifies to the limits of the perspectival system since one cannot represent within single point perspective: the sky without measure, the wind blowing the clouds. The mirror, writes Damish, is thus an ‘epistemological emblem’ that “reveals perspective as a structure of exclusion, the coherence of which is founded upon a series of rejections, and yet which has to make room for the very things that it excludes from its order” (Damisch 124). In Damisch’s analysis, /cloud/ becomes a sign of the constituent outside of the perspectival system.

JMW Turner was Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy in London from 1807 to 1837.

VIII. CONSTRUCTION

A figure. He is seated. Left leg folded toward right hip; right leg angling to the floor. His toes are slightly upturned, metatarsals straining through the thin skin of his top-foot. He props himself against the wall with his left upper arm between the shoulder and the elbow joints. His right hand rests lightly on the surface in front of him, each digit stretched in longitudinal arch; his palm is domed slightly. His torso twists to the left along a curved column of spine, while an opposing articulation of neck rotates his head to the right.

Their heads, in response, are angled. Eyes cast over firm flesh and shadow. Hours and minutes translated into shape and shade; desire into object’s outline.

Now the central, all-seeing Eye is a hundred, thousand looks. Architecture become archive.

IX. COSMOS

From one cosmology to another there is simply a difference of scale, which is to say relationship and to suggest that they continue, one into the next – element … molecule … grain … formation … landscape … system … galaxy … universe – that it is only our perspective that alters and, with it, the stories that change.

First: ‘A History’

In March 1969, the astronaut Russell Schweickart spent just over 241 hours in space where he tested the Portable Life Support System that was later used by the 12 astronauts who walked on the Moon. During the mission, a technical error left Schweickart unable to re-enter the spacecraft, instead holding onto the outside of the vehicle with one hand. With reference to his experience watching the earth from this vantage point for hours on end, Schweickart writes in his essay ‘No Frames, No Boundaries’: ‘You look down and see the surface of that globe you’ve lived on all this time … [a]nd somehow you recognize that you’re a piece of this total life.’ Schweickart was born in 1935 in Neptune, New Jersey.

Second: ‘The Metamorphosis’

The ears of the rabbit become the antennae of the cockroach; the shell of the cockroach becomes the tooth of the rat; the tail of the rat becomes the trunk of the elephant. The trunk of the elephant sweeps away those of the trees. A space clears. All is a quality of light, including all matter and all energy.

Third: ‘Myth’

A flower blooms, where each drop of blood stains the earth.

Now: ‘A Parable’

A man enters. He is wearing orange clothes and carrying a book. The sign on the window sill reads ‘SILENCE’. He shuffles past with bare feet. Meanwhile, outside, a crowd is gathering ...